BIOGRAPHY

M'Hamed Issiakhem

About

Here it is about a synthetic biography of the man and artist M’Hamed Issiakhem, and its content tries to remain as factual as possible.

The angle of view emphasizes the artist’s legacy, a legacy that his work and remarks explain with a depth of sharpness.

Everything is reinforced in this text by the elements of the documentary background and the testimony of the closest.

Childhood

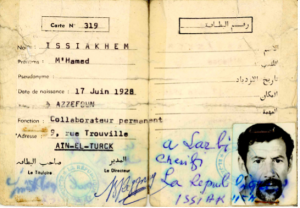

M’Hamed Issiakhem was born on June 17, 1928 in Douar Djennad a mixed commune of Azzefoun in Kabylia. This region of Aït Djennad has known as elsewhere a thin sword partition of the last French colonizer, with the decree of 03 February 1895. Thus, the indigenous population had at the birth of M’Hamed Issiakhem already experienced exile to escape colonial rule, and seek better fortune in Berber territory and historic coastal trading posts . It is in this douar that the town of Taboudoucht will be particularly loved by the painter, a commune that will exist as such much later, erected by order of 30 November 1956.

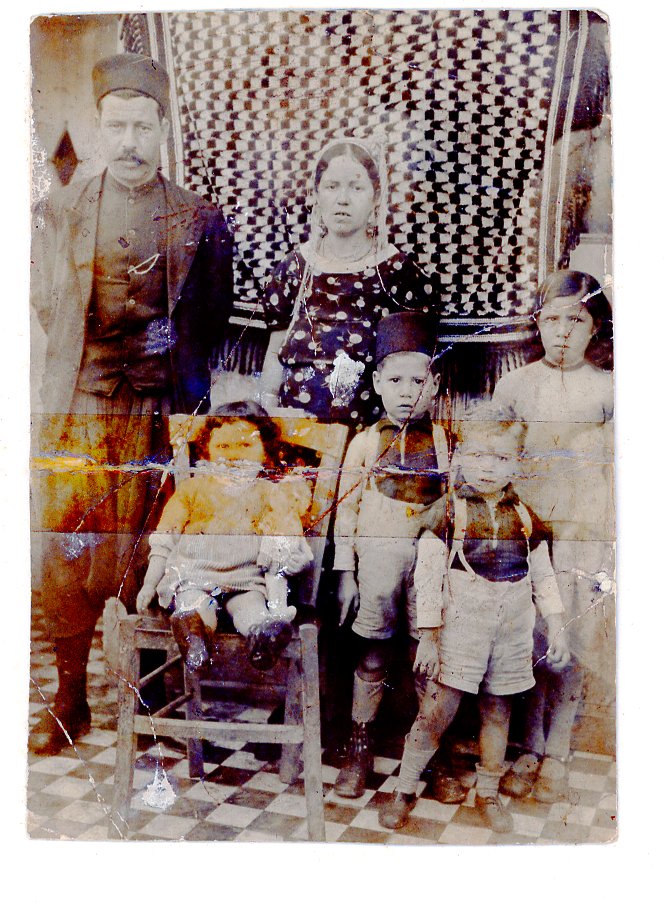

The eldest son of Amar Ben Arezki and Oughemat Ouardia bent Mohammed, his paternal family had a Moorish bath at Relizane Market Square. From his real name Mohammed, he would later prefer the contraction M’Hamed.

As a good eldest son and at the age of three he accompanied his father to Relizane, thus opening the first episode of a long series of separations and missed appointments with his mother. She will remain in Kabylia and join them when he is twelve years old. In the meantime M’Hamed Issiakhem will be supported by surrogate mothers employed by his father.

Picture of his family from the document background

Difficult to measure the distress of separation and that of the long and painful journey. The upheaval of the landmarks that was this uprooting from the mother and the country of birth.

He evoked this episode in the Révolution Africaine newspaper of July 1985 as a haunting dream.

« I stayed with the memory of my mother’s colors. My mother was very rich in colors, very rich in colors. These are the colours that come back to me. These are the colours supported by a mass that is my mother’s. Violent colors in hot fields. Especially in summer, summer… I see his walk, I see his bare feet, I see the poppies, I see the wheat… I still remember a cow, a goat… It’s very vague in my memory. It’s vague. But I see these bright colors, these burning colors. I still see myself following her and very sensitive to her back, to the colors she carried despite herself. She didn’t even know she was carrying color. For her, she covered herself with a flowering cloth… I was always thirsty when I was around my mother or when I was following her. And then we broke up.”

He completed his schooling at the Indigenous school where he entered in 1934 until obtaining the certificate of elementary primary studies, a trace of which is still available in the registers of the school of Relizane. He then already showed particular predispositions for drawing, and even obtained a prize from Marshal Pétain awarded to the best work. Recall, and De Gaulle will remember later, that the colonial France of Algeria supported the Marshal in a rather majority and often ostentatious way.

class photo in Relizane (Document background)

He had a happy and full childhood surrounded by many comrades in a family of relatively wealthy traders. He will know the militant camaraderie of the Muslim scouts of which he will be a part, comrades that the war will later take away one after the other, in conditions that will deeply mark man. M’Hamed Issiakhem took the lead and the innocence of this childhood will be shattered following a tragic event that will mark the artist and his family forever.

Following the American landing of 1942 with its procession of military and armaments, the children of Relizane, carried by the natural curiosity of these ages, eventually attracted the sympathy of the American military, and were tolerated in their proximity.

American troops landing exercise near Algiers in April 1944. Wikipedia source

Curiosity that led M’Hamed Issiakhem to seize in July 1943 a grenade from an American depot, certainly encouraged by his fellow scouts of whom he was the designated volunteer. This grenade supposed to be disgorged has found itself operational. And the rest was inevitable.

He will bring this weapon that he supposes harmless to the family home, and handle it surrounded by his loved ones. And then there is the explosion. Or as he will call it by this dialectical euphemism “Tkelmet” “translatable by “she spoke”. But this grenade did not just «talk», it screamed very loud while spitting around it metal and fire fragments.

This resulted in the deaths of two of his younger sisters Saadia and Yasmine and his nephew Tarik. Yasmine’s younger sister died later in painful circumstances that will certainly constitute a psychological fracture from which he will never recover.

Three other family members were also injured. He will miraculously emerge alive at the cost of a long and painful hospitalization that took place over a period of two years. Period of infection, gangrene and return to hospital for additional amputations of the left forearm. This will happen three times before disarticulation. It will also leave a phalanx on the right index finger and many other injuries.

In addition to the unbearable physical pain, at a time of war scarcity when Dakin’s water was being treated, there is the memory of the last look of his little sister Yasmine, whom he was very close to. For this younger sister, he was that big brother whom we admire and follow everywhere.

She will die from her lung injuries. M’Hamed in agony will keep only a vague memory of this moment, but he will keep in memory the pain of his mother who prayed to all the gods that they concede a chance, even a minute, that his daughter survived.

The death of his little sister Yasmine will certainly have a considerable impact on man and his work. But not only. This is only the beginning of a life of trials that cannot leave anyone completely unscathed. This is also the beginning of what will be the second episode of separation with his mother.

Added to the intense physical pain of amputations, the bursts of which he is rid of in unity and with a sharp wound, he will be crushed by an ever heavier guilt as he recovers and becomes aware of the desolation left by the explosion. He will then have to face the gaze of a grieving mother, a look of deep pain that does not reproach but absolves nothing. Forgiveness is impossible, indecent, unnecessary. A mother who decades later, when her son unexpectedly visited her in Oran, locked the door of her room so that M’Hamed did not see the photo of her sister on the bedside table. When this door was opened to him through the evil hearing, he saw this frame and slept with it.

And as if all this were not enough, he had to face the heavy and compassionate looks of a city on a human scale, marked by this event. He tried to find his place. And when he heard the mother of a possible wife asking his wife for a more substantial dowry for the penguin she saw outside, he understood then that he had nothing more to do in Relizane. He made the decision to leave behind a mother in pain, and a grieving father of the ambitions he had for his eldest son.

He eventually left home and took a train to Algiers in 1947. He was eighteen years old. He will thus raise up the injunction of his mother who did not allow him to lament «I did not give birth to you infirm.» she said. What he later described as an act of filial love, though he would inevitably bear the burden of the survivor’s guilt and by the same token the duty never to bow down.

«I was seriously on the edge of the abyss. It was absolutely necessary to find some kind of diversion. I had to find something of my own. Why? Because we have always considered as incapable, impotent or whatever, infirm. » «Excerpt from the film directed by Fawzi Sahraoui, broadcast by Radio Télévision Algérienne on December 1, 1985».

He will have a tumultuous relationship with his mother for the rest of his life, but an unbreakable and powerful bond. To understand its intensity, let us accelerate the time decades later when M’Hamed Issiakhem fought against the Cancer that will win in 1985. His mother, visiting him in Bainem, quickly understood, without our secrecy, that this evil was the one that took away her husband in 1971. She rose with a stroke, and with a sentence that sounded like a sentence to her daughter-in-law in a calm and resolute voice, “it is indecent that a mother should leave after her son.” A few months later she left us with a devastating cancer.

This event sheds light on the complex relationship he had with his mother, it is also this dignity of Algerian mothers that the painter will seek all his life to exalt with a boundless fascination. He will testify to that many times.

It is thus in Algiers and among relatives that his adult life will begin.

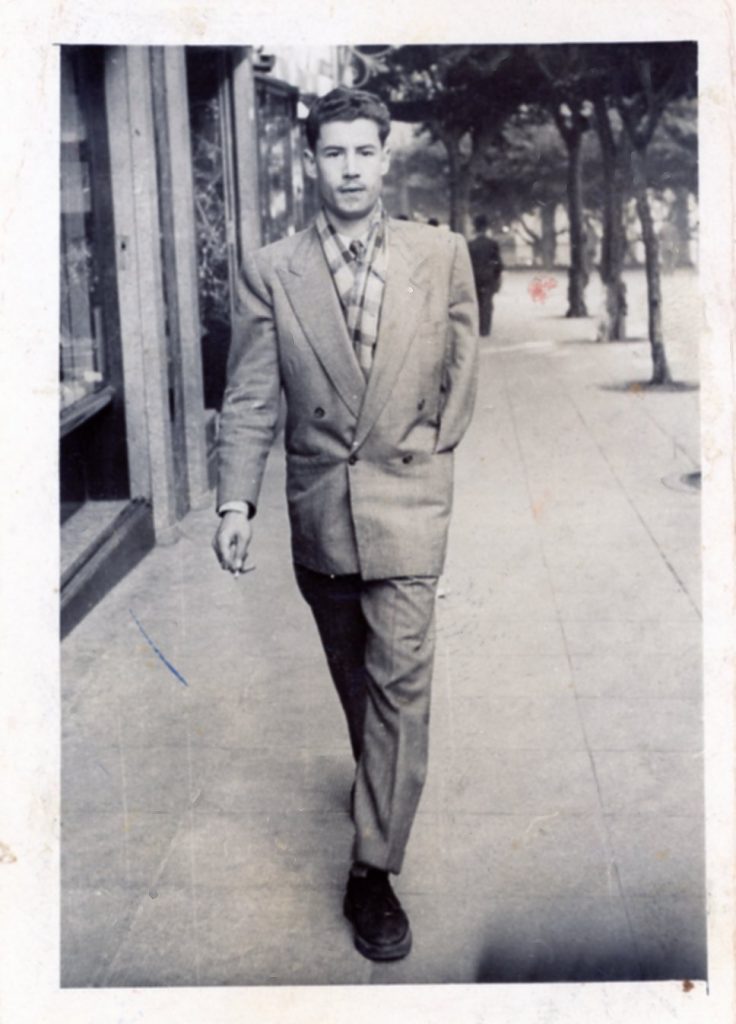

Young Adult

A life where personal and Algerian drama will merge into an artistic vision that he will constantly seek to refine and develop.

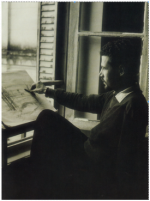

Anxious to prove to himself and to his family that he was not reducible to his handicap and that he could also provide the bread and the basket, he considered exploiting his gift for drawing, a gift that a nurse helped reveal during her hospitalization in Relizane by providing her with sheets and pencils.

In Algiers he enrolled in the Fine Arts Society. Soon noticed for his abilities, he joined the National School of Fine Arts in Algiers, where he took courses in round-the-hump, anatomy, Muslim art, painting, modelling, art history and engraving.

He won the first prizes for illumination, ceramics, engraving; the second prizes for round-bosses, academies, paints (drawing academy and painted academy), drawing living models; the second mentions in drawn torsos and painted portraits.

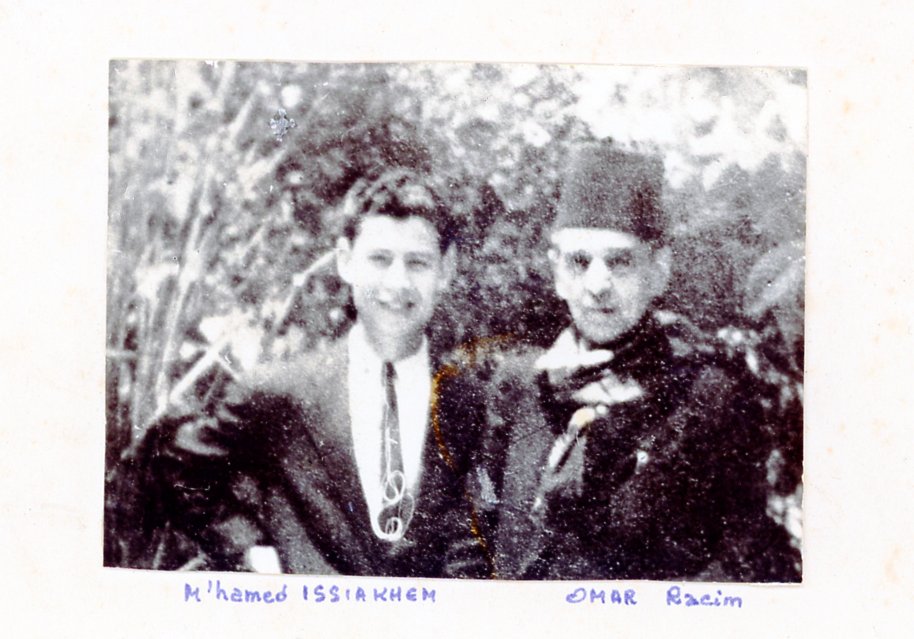

While studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he took courses with miniaturist Omar Racim.

In the 1950s, he obtained a scholarship that enabled him to take engraving courses at the technical college of Estienne in Paris.

Here he is embarked on the artistic adventure by default. It is necessary to understand the man he was, and his fierce demand for himself and his art, to integrate the way he perceived the path that led him from the first prize of the Marechal Pétin to the school of Relizane to his entrance to the fine arts. He summed it up better than anyone in an interview for Révolution Africaine of 16 to 22 May 1985 directed by Ahmed AZEGHAGH.

Photo of the painter with Racim: extract from the documentary background

« I went to painting by accident… Painting hurts me. When I paint, I suffer. It may be a form of masochism. I am a painter, or consider myself a painter, but for me it’s always in doubt. Because I don’t know what it means, a painter… A painter, for me, is a vague, distant notion… Let’s say I paint. Why do I do it? I wonder that too. I did not come to painting as French, Spanish, Italians… They go to painting quite normally. They have landmarks, traditions, most come from an already cultivated environment. They were born with music, with the arts, they went to the theatre. While I, going to paint, I consider this to be the biggest accident I may have suffered in the course of my existence. He may be more terrible than the one who provoked my amputation…

At first our parents did not give free rein to our inspiration. They did not put at our disposal pencils of colors, brushes, gouache… We, when we drew at home, the father would come and say, what is this? And we were getting punches, because drawing, it meant we were wasting our time. So, from our earliest childhood, we were cut off from drawing and painting. I can’t tell you if I liked drawing or not at the time. Besides, I don’t know if I like drawing or not. Drawing, in my opinion, is something innate in the human being. Almost a reflex.”

It is at this time that he will meet his first companion Georgette Christiane Pelcat, with whom he will have a daughter on October 15, 1951 and who will be named Katia Patricia.

In 1951, his classmate in the fine arts of Algiers Mahmoud Choukri Mesli will introduce him to Armand Gatti who came to cover for the newspaper « Le Parisien Libéré » the trial of the members of the OS (special organization), armed branch of the MTLD, and Kateb Yacine, with whom he will establish a special friendship.

«I met Issiakhem in 1951, in Algiers, with the filmmaker Armand Gatti. We drank together from the first day, and while I had just met him, he insisted that I go with him to Oranie, to his family, to Relizane. And since then, we’ve been pretty much together. We have a boundless friendship, because we often drink together whole nights, countless sleepless nights, and sometimes even day and night. And naturally, we talked a lot. I discovered a very great sensitivity, a very keen intelligence. M’hamed was able to have hundreds of friends, and he saw very quickly what was in any individual. Good or bad, and he said it. He hated hypocrites, and there are many.”

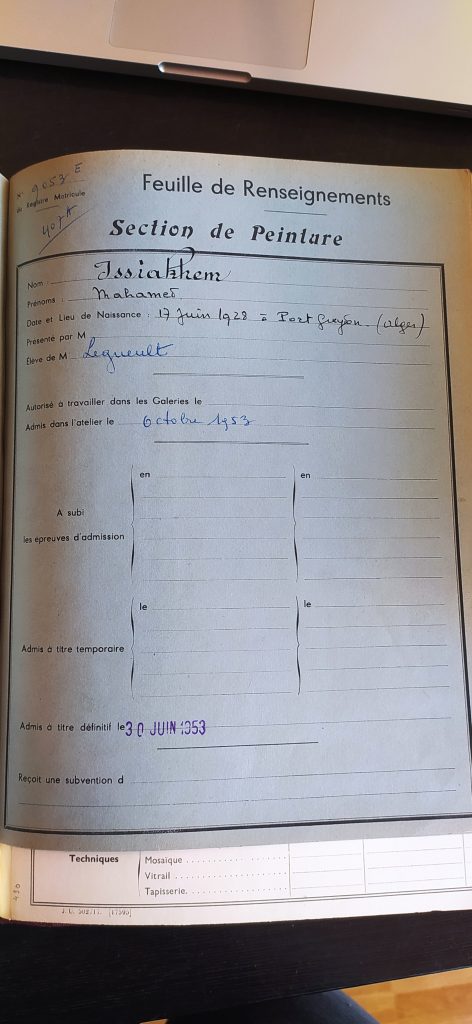

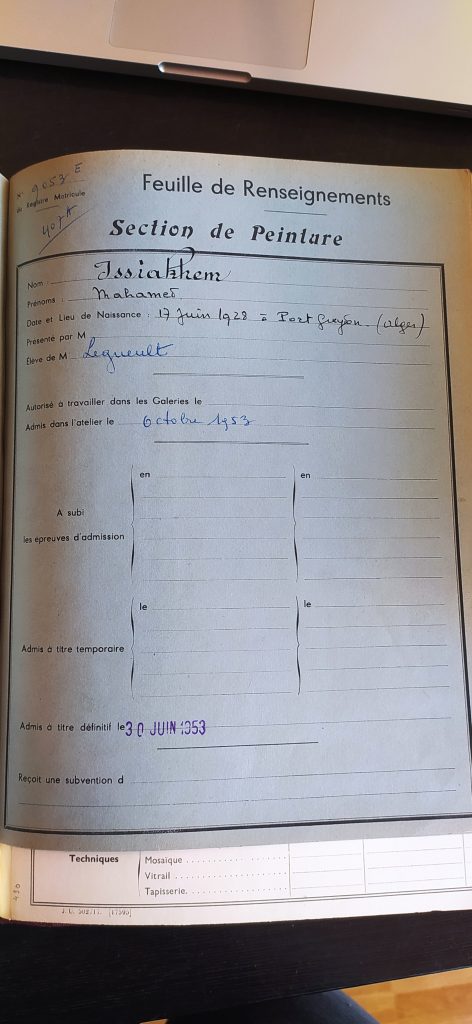

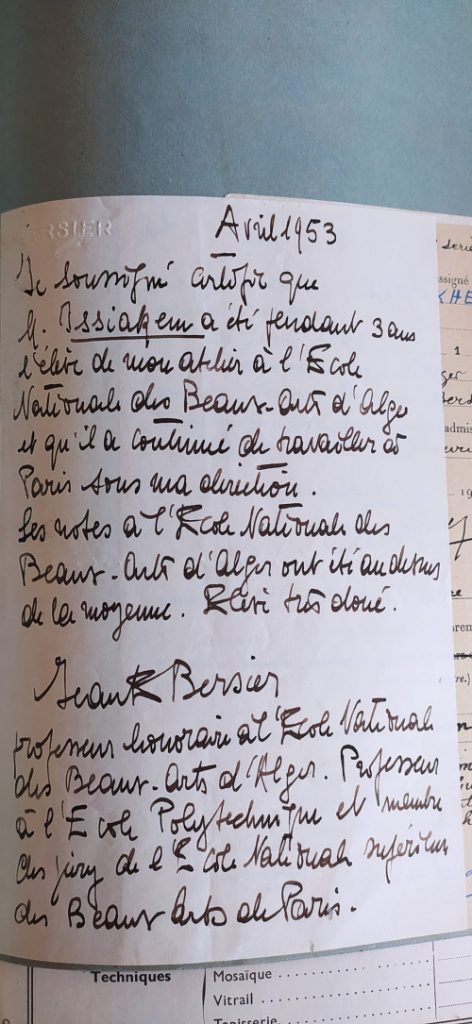

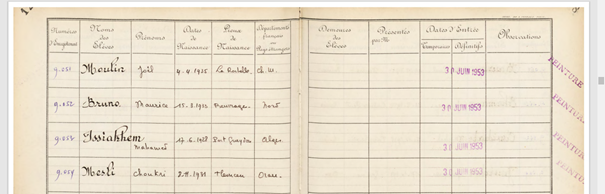

Encouraged by his teachers and many supporters, he was invited to the entrance examination at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts in Paris, which he attended from 1953 to 1958 particularly LeGueult workshop.

He will present the entrance competition and will be officially admitted on 30 June 1953

It will have a recommendation in this regard by Jean-Eugène Bersier

They will be registered there with Choukri Mesli in the Painting and Engraving section.

M’hamed Issiakhem will not stop militating and painting. In 1955 his painting « the shiner » was noticed at the World Youth and Student Festival in Warsaw (Poland). This lost work paid tribute to street children called the «Yaouled». They symbolized both the deep misery of the indigenous peoples, but also the hopeless childhood of these «indigenous» condemned by fate and their condition of colonization. They’d polish the shoes they didn’t have.

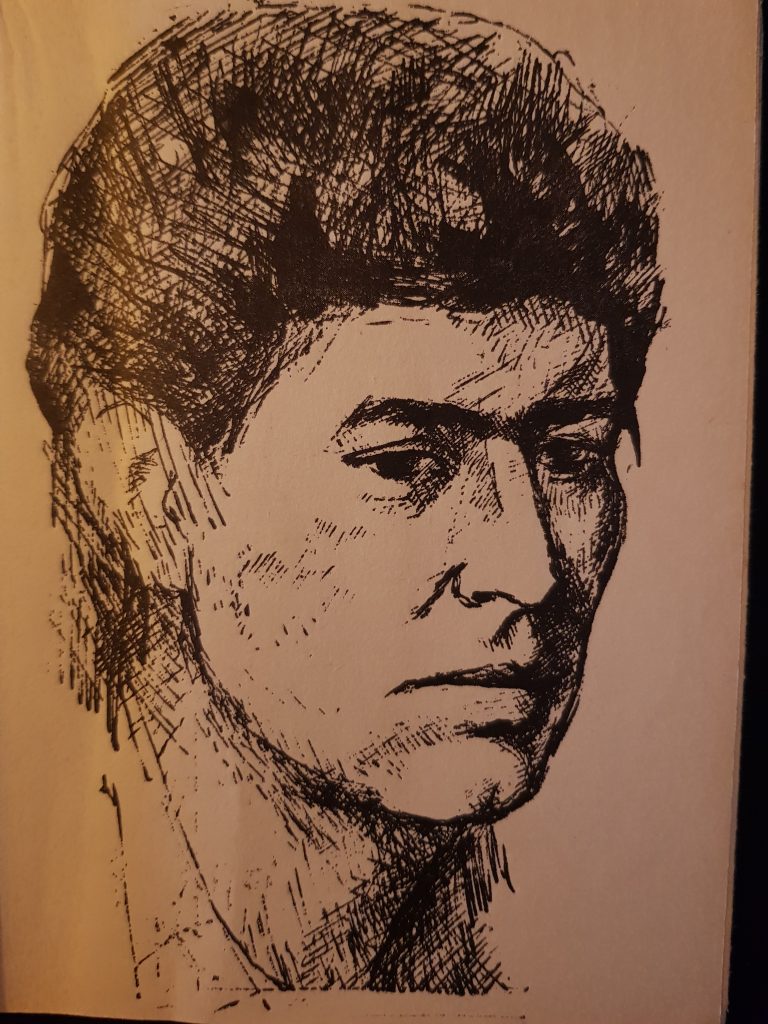

In 1956 he painted a pen-and-ink portrait of his friend Malek Haddad for the fourth cover of his collection of Poetry « Misfortune in Danger ».

Occupational therapy instructor in the department of Professor Oury at the psychiatric clinic Laborde in Cour-Cheverny, department of Loir-et-Cher, he obtained the prize of the Marine Cross for several works, including one, abstract, entitled The drop of blood. He refused the “Marine Cross Award”, awarded by the French Ministry of Health for his work in occupational therapy. He will say to justify it « I save your sick children while you murder ours

An FLN activist since 1956, he was mobilized in 1958 on instruction of the Federal Committee.

In 1957, his illustrations on the subject of torture in Algeria appeared in the magazine « Entretiens sur les lettres et les arts », special issue «Algérie» in February. His portrait of Djamila Bouhired is used by the FLN in its propaganda and information media. Thus, the representation of the FLN in Germany exploits it in the form of posters and postcards. “The idea of painting the woman came to me,” says M’hamed in 1969, referring to Djamila Bouhired, the tortured women. Since then, I have only dealt with women, with torture, to this day,” he added.

He spoke more about this in Révolution Africaine Newspaper of 16 to 22 May 1985 directed by Ahmed AZEGHAGH.

«I am very faithful to the condition of the woman who lives intensely her condition as a woman first. The woman…

But it’s a very abstract subject! It’s a very abstract subject that puts me first from the plastic point of view… What is the woman for me? That’s the source. It’s a huge, unlimited subject. You will notice in my work that it is apparently the same character who returns, but tell me if there is no difference between one work and the other. Looks like all our wives! No, it’s the same one that is changing, evolving, degenerating, progressing and all that at the same time. It’s a kind of game between her and me. In fact, she is the one who helps me to go further and further. I say that motherhood is the best…(6).”

Wanted by the French authorities, he went into exile in the GDR where he lived in 1959.

M’Hamed Issiakhem exhibits at the Donilstraz gallery in Leipzig. His works will also appear in the exhibition organized in 1960 at the « Club des Quatre Vents » in Paris, by the North African Group of which he is a member.

In 1962 he boarded the Casa Velasquez in Madrid, where he did not stay to join Kateb Yacine in Paris, then Algiers in his company.

With the approach of independence he will indeed be contacted in Spain to join Alger Républicain in Algiers, what he will do with Kateb Yacine joined in France before their departure for Algiers.

He contributed until 1964 to this journal, in which he published drawings.

Activity he continued for other publications.

Founding member of the Union Nationale Des Arts Plastiques (UNAP) in 1963, he joined the year after the Ecole Nationale d’Architecture et des Beaux Arts d’Algiers where he directed a workshop.

Appointed in 1966 as professor of the School of Fine Arts of Oran, he also teaches there.

A period punctuated by “chapel” conflicts, some would say, of opposition between figurative and abstract, others would say, these will be substantive debates in reality and on which it is essential to pause for a moment.

Stop there, but without anachronism or misunderstanding. All the Algerian artists of that time were heroes, and M’Hamed Issiakhem will not fail to recall this in the

Excerpt from the film directed by Fawzi Sahraoui, broadcast by Radio Télévision Algérienne on December 1, 1985.

Thus, it is common to speak of the opposition of M’Hamed Issiakhem to the Aouchem current founded by Mesli and Martinez.

On this subject, M’Hamed Issiakhem spoke in Algerie-Actualité of week 14 to 20 of July of the year 1968, interviewed by Zhor Zerrari “Painting, as in any art, demands a minimum of truth, demands truth about oneself. … The best evidence is that they created Aouchem – They imposed an ancestor on us.” That’s pretty direct.

He considered that art had a particular mission, in his country recently decolonized and whose identity had been deconstructed by long periods of invasion and brutal colonization.

The period was already well agitated within the Algerian society itself. To the joy of independence quickly followed profound disappointments. A flash civil war in the regions of Kabylia that would experience a erasure of decades of this original identity of the Algerian people. As for the dream of freedom, it quickly crashed on the tanks of the border armies in 1962, on the one hand, armies waiting behind and far from the front, and on those of a coup d’état in 1965 on the other. As for the assassination and imprisonment of historical liberation activists, this was no longer a taboo.

M’Hamed Issiakhem, and others, had understood that the actors of what will be thirty years later the scene of the ten dark years of terrorism, were all already behind the curtain.

A certainty for the painter; this identity could not be reduced to the limits proper to the artists.

In El Moudjahid, 19th of April 1969 interviewed by Halim Mokdad, he used the words “… If the painter does not live, does not explain the drama of his society, he is not an artist…”

It was unacceptable for M’hamed Issiakhem, and let’s say dishonest, to start the story by the end. He spoke in this capacity in Algerie-Actualité week 14 to 20 of July, 1968, interviewed by Zhor Zerrari.

«They have fun, mock the people. When we ask them to try to understand their art, the why of their art, the answer too is “you understand… it is not defined, it is difficult… You know Abstract painting…” The painter’s duty was to think of those who were with them, those who lived around them. For everyone can love painting. Everyone loves painting».

To which he will add in El Moudjahid, April,19th 1969 interviewed by Halim Mokdad

«I play the role of the painter in our country. Any stagnant art is a retrograde art. Any art that wants to be ahead of the people is a pretentious art, dishonest…»

It is from this search for the deep identity of the Algerian people and its singularity that the painter’s obsession carries. An identity battered by one hundred and thirty years of brutal colonization, deportation, dismantling, which were superimposed on thousands of years of internal wars and successive invasions Phoenicians, Roman, Vandals, Arab, Ottoman…

«We must constantly respect this people by remaining at their level and evolve with them. We must find this Algerian pictorial personality. I’m looking for myself. I didn’t find it.

… Now, some have wanted to impose a very specific orientation on painting. The painter’s work must be that of everyone. We’ve been so influenced, we don’t have a personality. When Kateb Yacine speaks of an ancestor on one of my paintings, he does not finish the word « unhoped for »; it is that he will always have hope. Figuratively, it is the expression of the drama of the Algerian. We must put plastic art at the service of your people»

El Moudjahid, April,19th 1969 interviewed by Halim Mokdad

The painter M’Hamed Issiakhem will work his whole life to exhume the soul of his people, to reveal the profound truth through the faces and textures that surround them. He will fight relentlessly against the snobbery in art, against this self occupied with long chatter around works supposedly too complex to be understood by the people.

Even worse, by observing the denigration of the country’s artistic history by seeking a starting point in the Neolithic. Thus, neglecting the inheritance of the Racim brothers constituted for M’Hamed Issiakhem a quasi-revisionism. Kateb Yacine responded to the injunction to reject everything that the Algerian had acquired during the colonization, including the French language, “it was my war booty.”

Here’s what he said in Algerie-Actualité of the week 14 to 20 of July, 1968 interviewed by Zhor Zerrari.

If there’s tradition, culture, talent, it’s Mohamed Racim, so why ignore Racim, why refuse to go to Racim’s school. We murder miniaturists and highlight painters. We ignore miniaturists but we talk about miniature.”

It is a matter of promoting a future that does not clean up its past, but on the contrary assumes all its dimensions

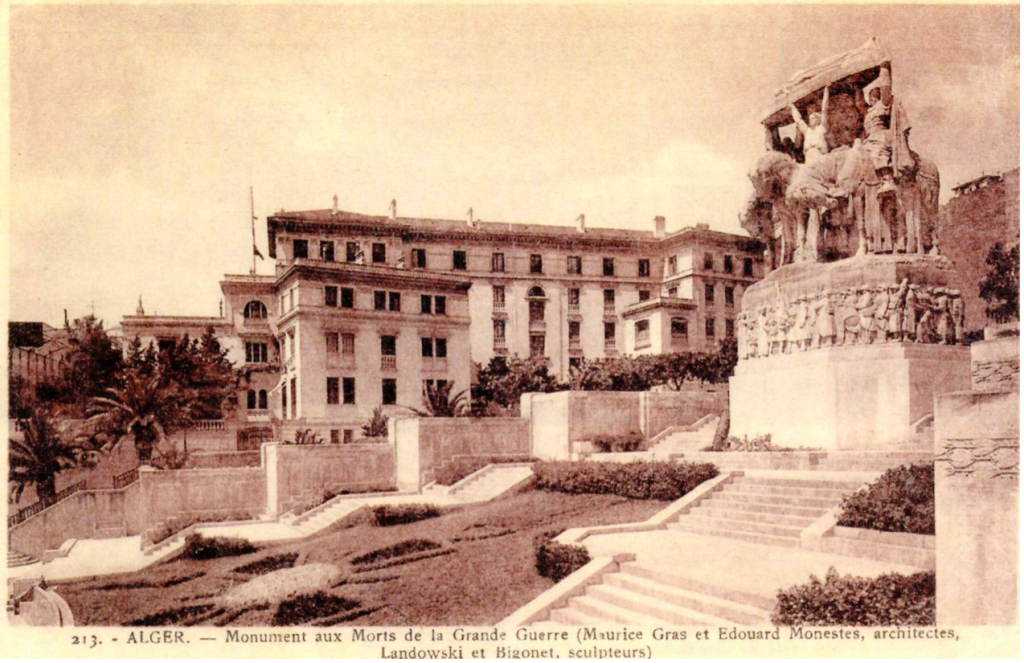

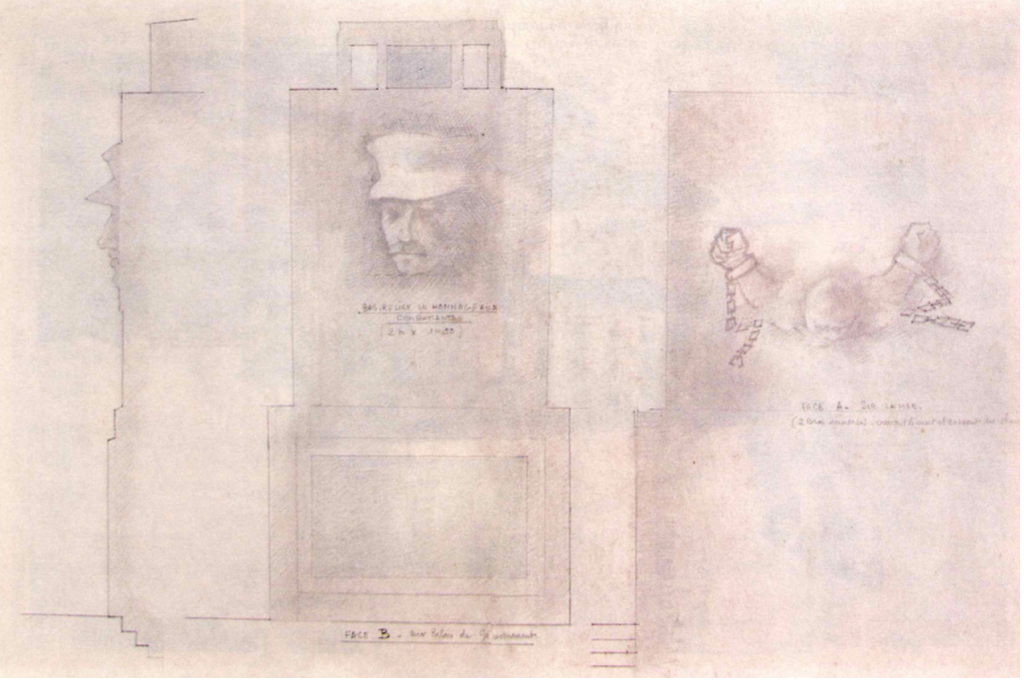

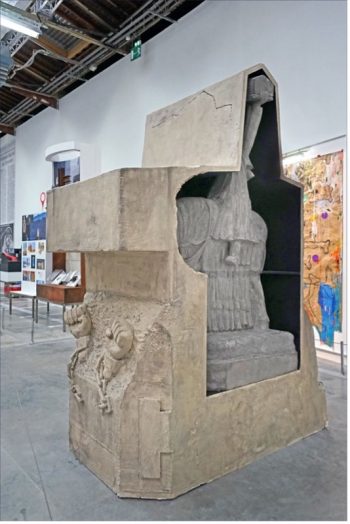

He applied this same precept when he was asked in 1978 to protect the First and Second World War Memorial in the Pasteur Avenue clock garden with a bas-relief. A monument that should have gone back to its supposed French owner, engaged at the time in a campaign to recover the artistic heritage left on site. This monument signed Landowski is still carefully protected by this sarcophagus.

This observation could be generalized to all sectors; political, religious, linguistic… The erasure operated by the colon continued his work. The support of M’Hamed Issiakhem to the rioters and artists threatened during the Berber spring of Tizi Ouzou of 1980 testifies to this. However, he would never see in his lifetime the Berber regain his place as the official language of Algeria.

Thus, to reduce the debate between these artistic movements to mere parochial quarrels is an anachronistic simplification. The fundamental stakes were that the newly decolonized Algeria meant of itself, of what it was and especially of what it wished to become.

This is what the artist stubbornly tried to accomplish, finding the Algerian pictorial personality, outside chapels and especially «leaders».

« Because a country without a painter without poets, without culture is a dead country. It is precisely after independence that you have the feeling of being seriously engaged. It is then that you realize that there is a great confusion among painters, The objectives of some are not the same as those of others. You feel like we brought them together for the better. You realize that they don’t know each other, that they separate before they even discover themselves… In a country where there was no painting market, artists competed for favours from an audience that did not exist… We had to be together, let an audience out. Unfortunately some wanted leaders, schools… everyone wanted to be a shepherd, but a shepherd without sheep.

In short, we lack modesty. An artist who lacks modesty is not one

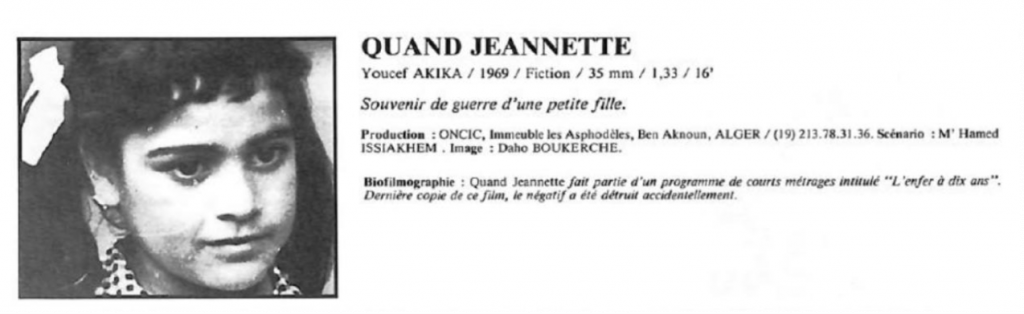

In 1967, he received the special jury prize at the International Television Festival in Cairo, and in 1968 in Prague for the production of the set of the documentary « July Dust » by Kateb Yacine. He also illustrates Nedjma by the same author at Editions Martinsard and signs the sets of the film « La voie de Slim Riad », awarded at the Cannes and Tashkent Film Festival.

He also directs the screenplay of short films

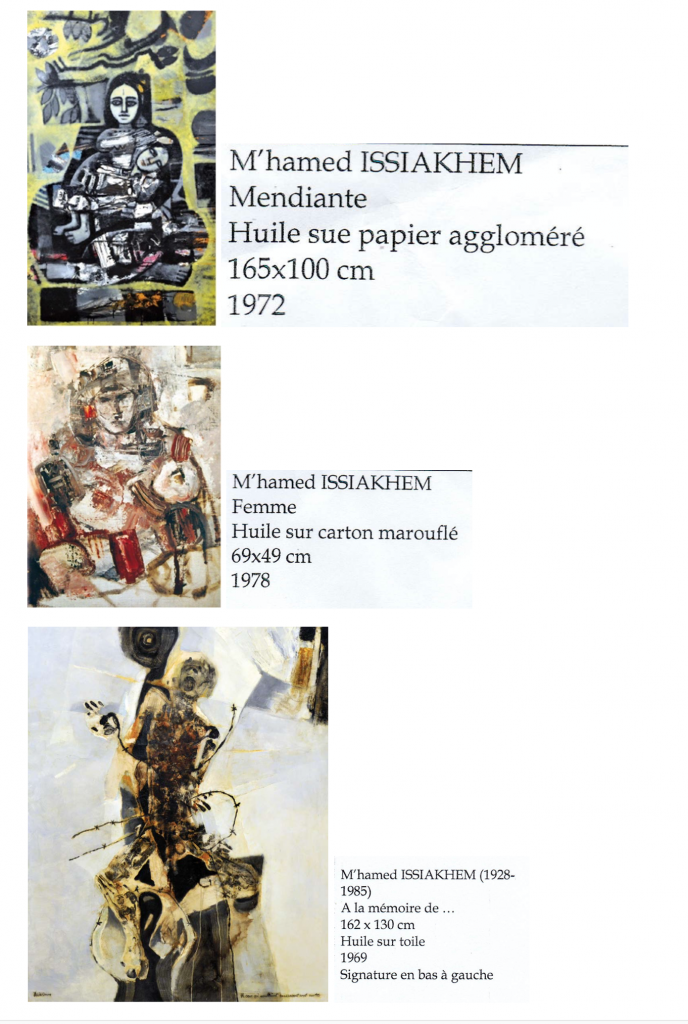

In 1969, the Jury of the first Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers awarded him the first prize for his painting entitled « A la mémoire de.. »

He accepted the position of professor of graphic art at the Ecole polytechnique d’architecture et d’urbanisme d’Algiers in 1971.

M’Hamed marries Nadia Meryam Cheliout on September 20 of this year. With whom he will have two sons M’Hamed and Ali Younes respectively born in 1972 and 1974.

In 1972 he will make a stay in Vietnam at war.

He subsequently stayed in Moscow from November 1977 to February 1978 to receive treatment.

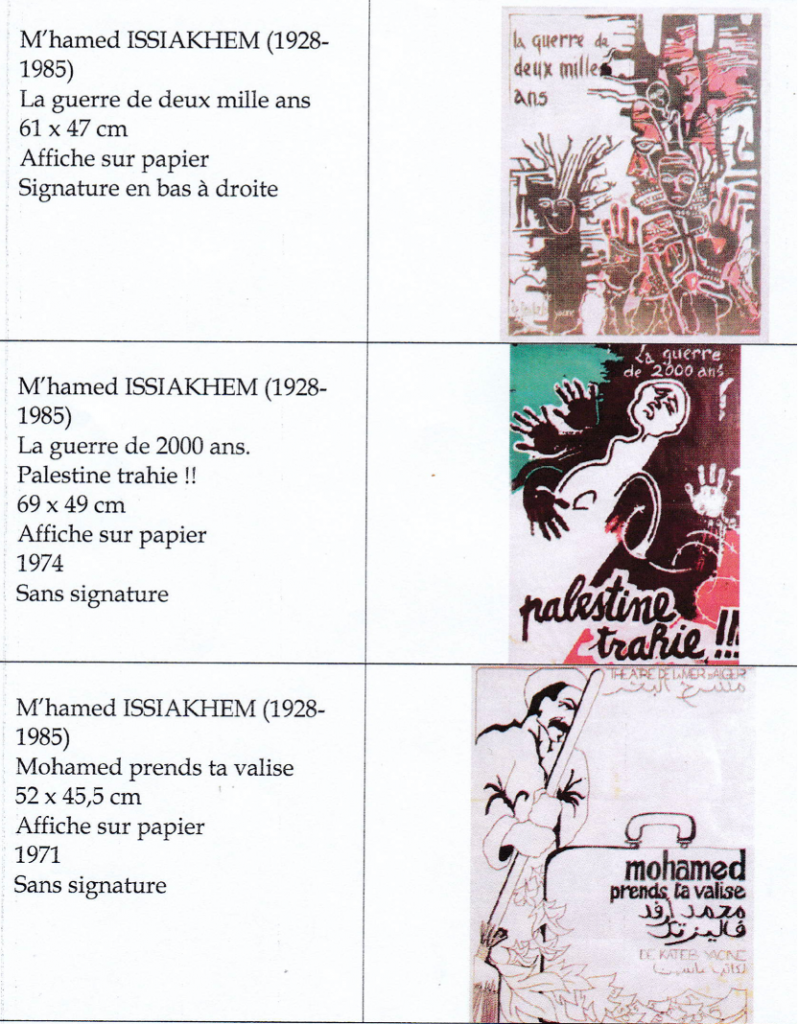

During this period M’Hamed will produce several posters for the theatre, models of postage stamps, models of Algerian banknotes, as well as those of Guinee Bissau and Mauritania

He will take part in numerous solo and collective exhibitions recalled at the end of this text.

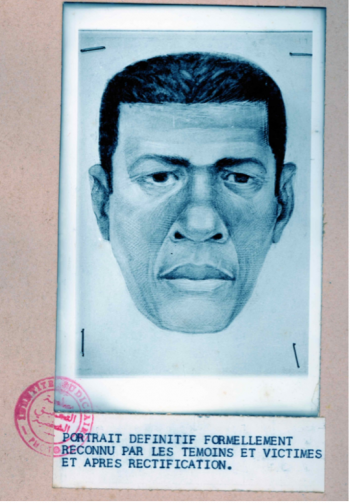

He also developed the uniforms of the police, the national gendarmerie and the crests

In this vein, M’Hamed Issiakhem was in charge of robot portraits within the national police. In charge of collecting the testimonies of the victims, most often rescued from the wanted murderer, he established the robot portraits on description allowing their arrest. This will allow at the end of the 70s to solve tragic cases that were chronicled at the time, including a famous case of rapist and murderer of multiple repeat children. The testimony of a little girl who escaped him miraculously led to his downfall

In 1973 he received the gold medal of the international fair of Algiers for his installation.

In 1978, M’Hamed covered the First and Second World War Memorial in the Pasteur Avenue clock garden with a low relief. This monument was intended to be unbolted and stored under cover before its restitution to France. The painter was sent to lock him in place behind a concrete cover. The artist did not sign this work which was to be anything but what it was intended for, a protective sarcophagus

In 1980 he received a first «Premio Simba» prize from the Simba Academy in Rome.

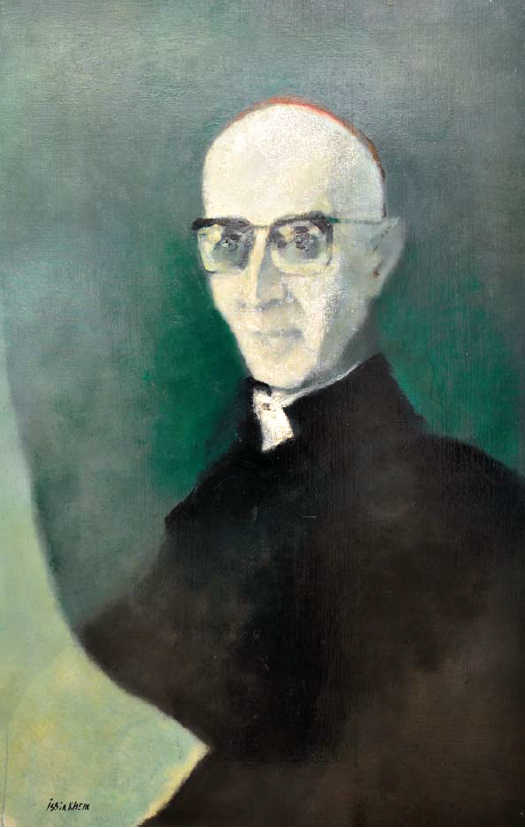

Other distinctions followed, including the Vatican Medal in 1982. He painted a portrait of Cardinal Duval

As well as the Gueorgui Dimitrov medal in Sofia in 1983 for his work « Dimitrov at the trial of Leipzig ».

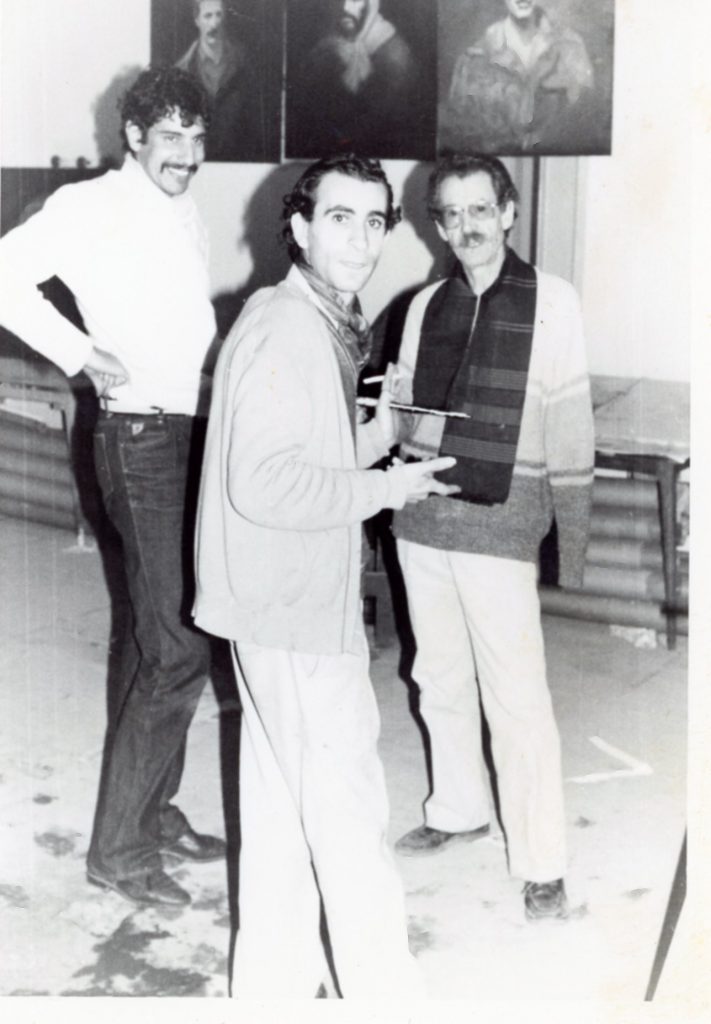

In the same year, he was artistic director of the Musée de l’Armée, where he led a team of artists to create portraits of Algerian revolutionaries and models of great battles. Still visible in the museum.

On the following photography the artist Mokrani in the foreground. True to his vocation as a talent developer, Issiakhem insisted that this artist join the team. Of an impressive culture, Mokrani was one of those geniuses of the century unsuited by nature to the reasonable framework of his time. A universal poet, a synthesis of Algerian genius drowned in a crazy world

At this period the first signs of the disease that will carry M’Hamed Issiakhem appear.

In 1985, his membership of the OCFLN (civil organization of the national liberation front) will be recognized for the period from 1956 to 1962.

He died of cancer on the night of December 1, 1985 in Bainem (near Algiers).

«Trade is the number one public enemy of art. When an artist does not respect his work, when he monetizes it, when he prostitutes it, it can give an idea of the causes of the slump… In truth the Algerian artist is turning his back on the national reality»

Painting must stop being the monopoly of a small class that can afford to buy paintings. We must therefore broaden the field, ensure that painting is accessible to the greatest number and not to a minority of intellectuals. The artist has to stop saying “I’m worth so much”. You have to accept that your work is financially worthless, or little, that’s how I see the activist of painting.”

»

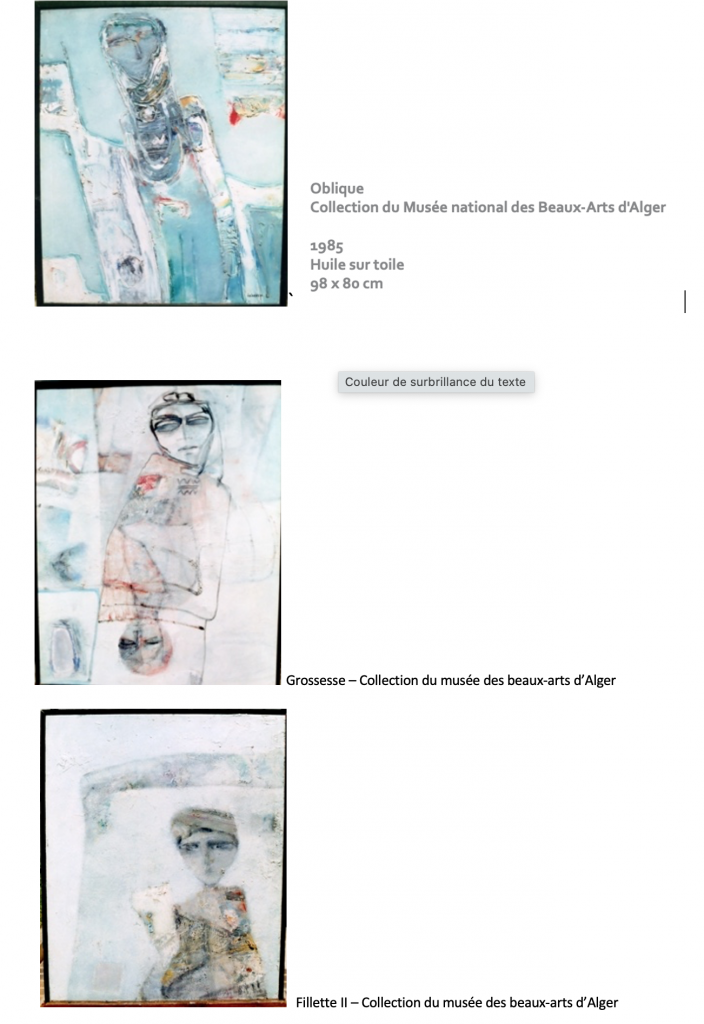

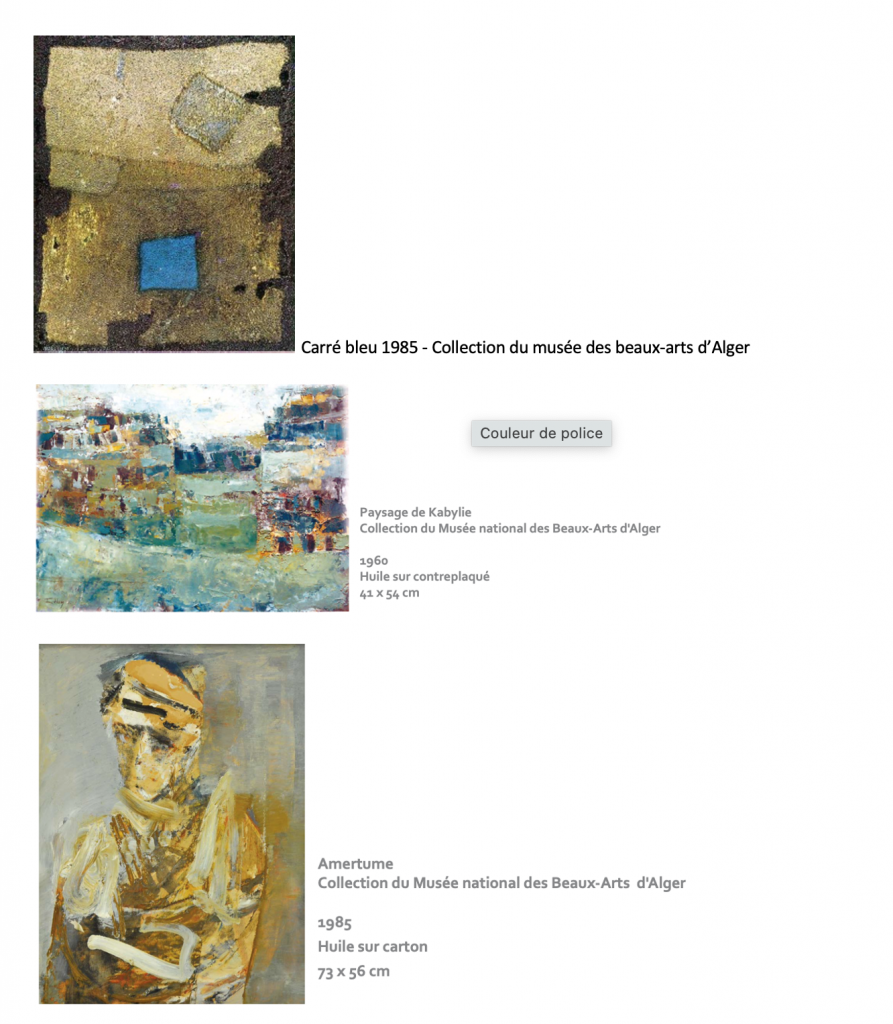

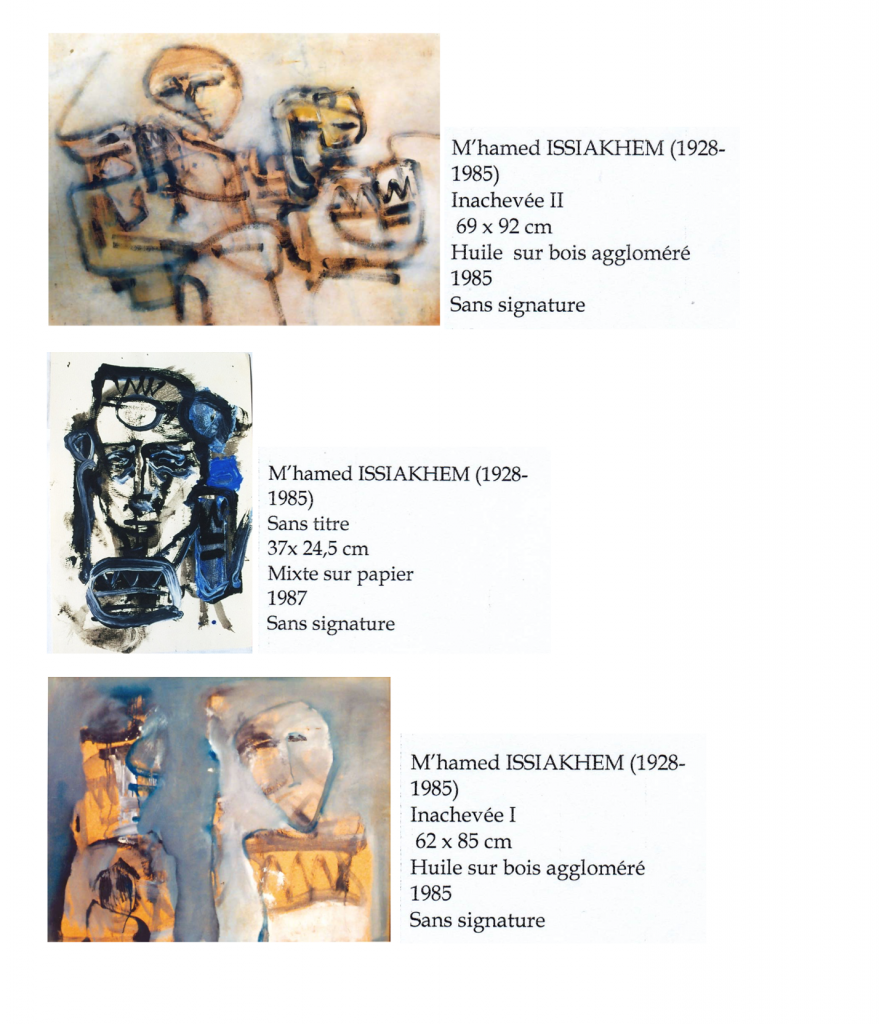

Thus, in order to be faithful to his memory, 6 works will be offered in 2001 to the National Museum of Fine Art of Algiers by his relatives. Pregnancy, Girl II, Berber Patterns, Blue Square, Oblique, Bitterness,

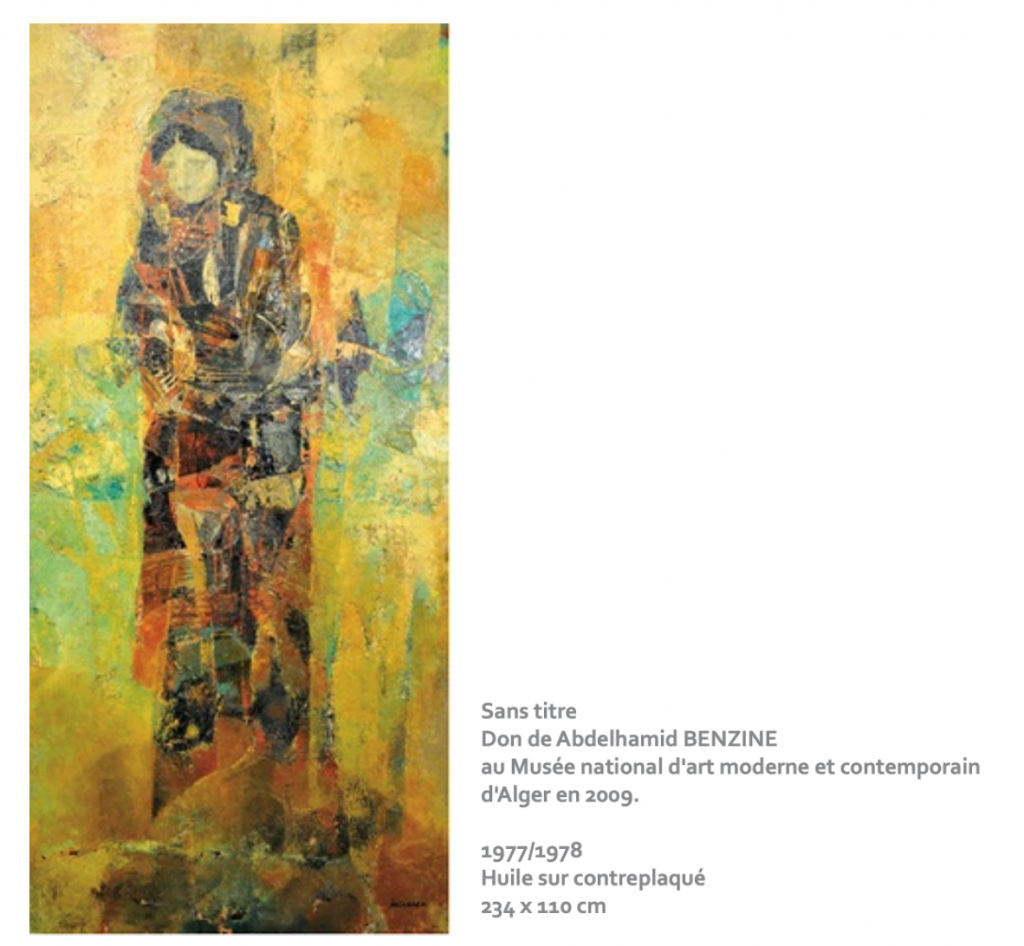

His long-time friends did the same, starting with Hamid Benzine at the Algerian Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

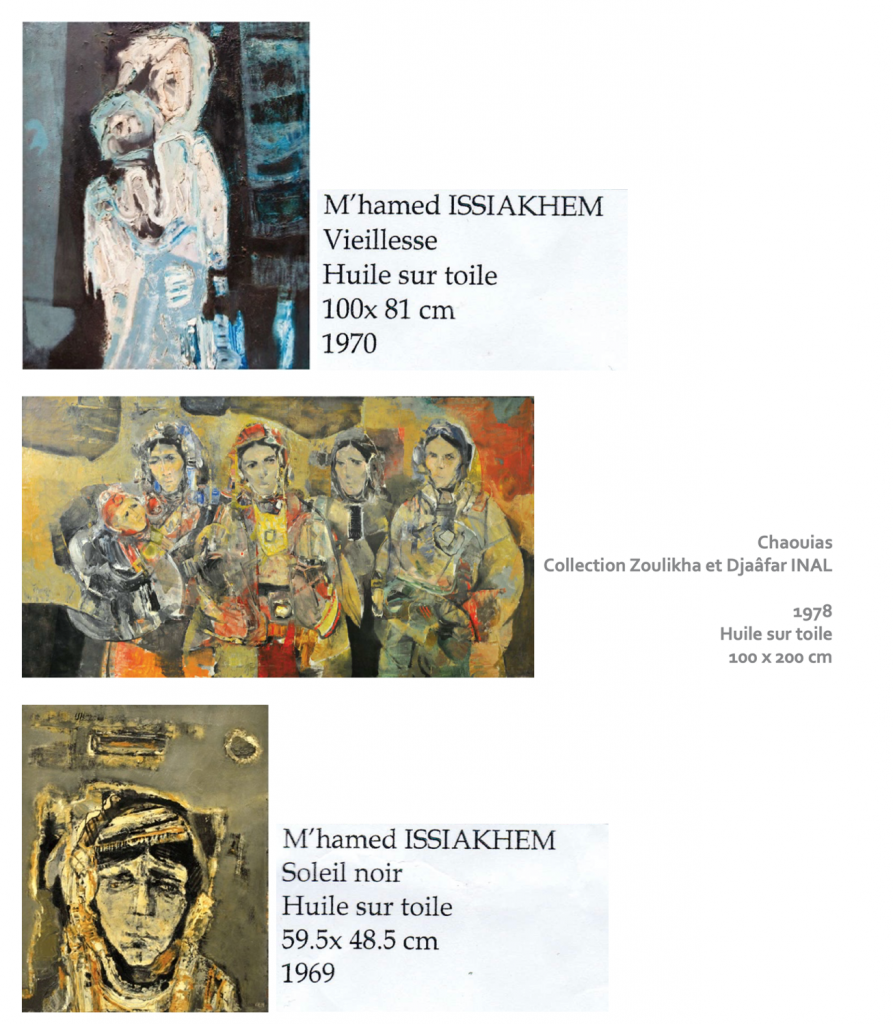

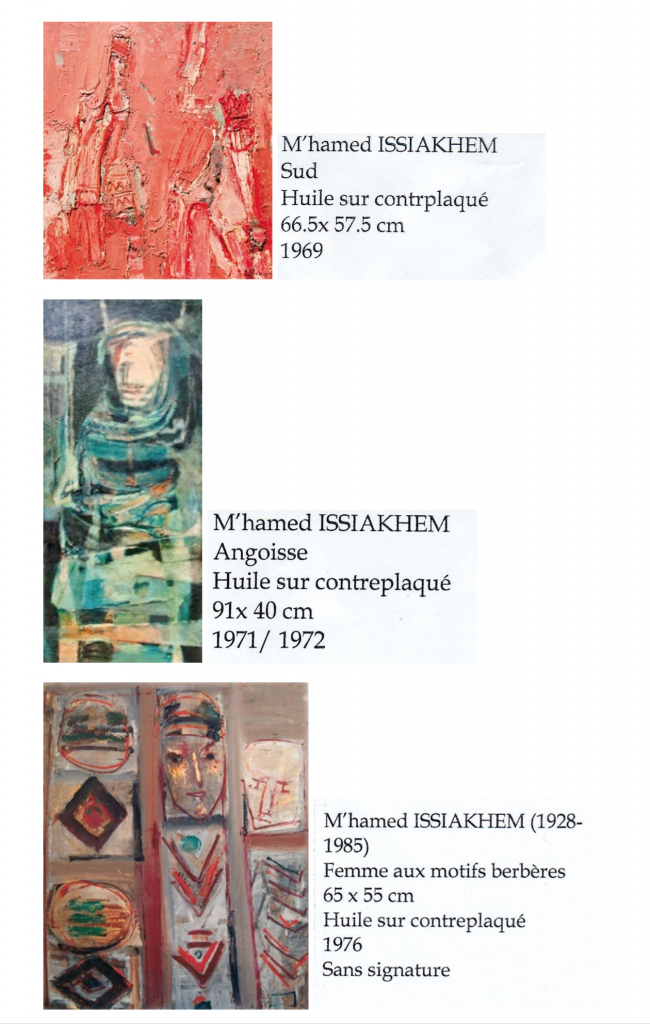

And later Djafar Inal and Zoulikha Benzine, both also long-time friends of the painter. Their donations, for which a non-exhaustive list is illustrated by the following, contain masterpieces.

On July 5, 1987, he was awarded the Medal of National Merit posthumously.

Distinctions

1941 | Prix du Maréchal Pétain (Relizane). |

1956 | Prix de la Croix Marine (en qualité d’Ergothérapeute).qu’il refuse |

1962 | Passage à la Casa Velasquez (Madrid). |

1967 | Primé au festival International du Film au Caire pour le film « Poussières de Juillet ». |

1968 | Primé à Prague pour le film « Poussières de Juillet ». |

1968 | Primé à Cannes et à Tachkent pour les décors du film « La Voie » de Med Slim Riad |

1969 | 1er prix du festival panafricain pour « A la mémoire de …» |

1973 | Médaille d’Or à la Foire Internationale (Alger). |

1975 | Primé au festival de Cannes pour les décors de « Chronique des années de braise » |

1980 | 1er SIMBA d’Or à Rome. |

1983 | Médaille « Gueorgui Dimitrov » décernée à Sofia. |

1983 | Médaille du Vatican décernée par le Cardinal DUVAL. |

1987 | Citation à l’Ordre de la Nation (Alger). |